SUP Magazine - Paddling Down the Amazon River - A Firsthand Account

AMAZONIAN FLAVOR PADDLING THE PLANET’S MOST DIVERSE DRAINAGES

Published in 2012 in SUP The Mag

As Published in Standup Magazine, 2012

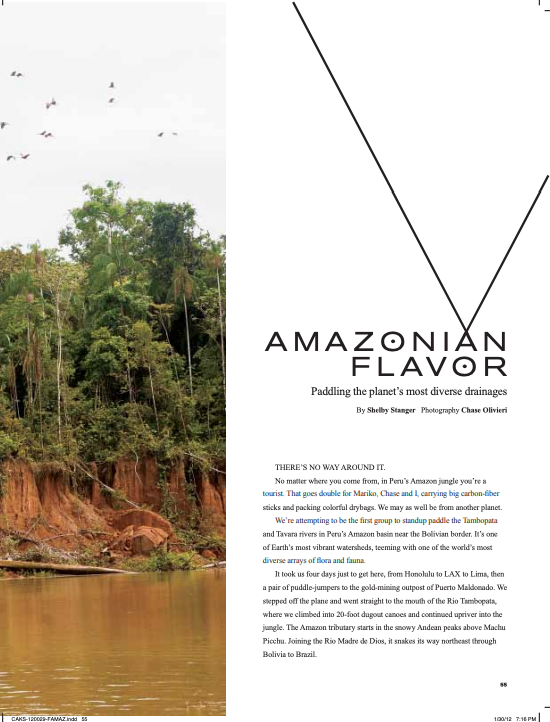

There’s no way around it. no matter where you come from, in Peru’s amazon jungle you’re a tourist. That goes double for Mariko, Chase and I, carrying big carbon-fiber sticks and packing colorful drybags. we may as well be from another planet.

We’re attempting to be the first group to standup paddle the Tambopata and Tavara rivers in Peru’s amazon basin near the Bolivian border.

It’s one of earth’s most vibrant watersheds, teeming with one of the world’s most diverse arrays of flora and fauna.

It took us four days just to get here, from Honolulu to LAX to Lima, then a pair of puddle-jumpers to the gold-mining outpost of Puerto Maldonado.

We stepped off the plane and went straight to the mouth of the Rio Tambopata, where we climbed into 20-foot dugout canoes and continued upriver into the jungle. The amazon tributary starts in the snowy Andean peaks above Machu Picchu. Joining the Rio Madre de Dios, it snakes its way northeast through Bolivia to Brazil.

There’s a a good reason no one has suPed this part of the amazon before or at least no one we’ve ever heard of. During the several hour canoe ride to our starting point we saw all sorts of critters shrouded by the endless greenery—some were friendly, like the flocks of butterflies, birds, fireflies, and fruit bats. others, like vultures, caiman (small alligators), capybaras (rodents the size of dogs), and millions of sand flies, were not so amiable.

The motley crew I’ve come with could hardly be further out of its element. Mariko Strickland is the talent on this trip. Though a relative newcomer to standup paddling, Strickland is turning heads, and not just because of her flowing dark hair, olive skin and softly chiseled physique. she won every event she entered at the 2011 Teva Mountain Games, and placed well at other big races on the mainland and in hawaii. Figures. She’s an unreal athlete: Prior to suPing, Mariko was a world-class soccer player with stints on the U.S. Olympic development and Australian national teams (her dad’s Australian, her mother’s Japanese).

Photographer Chase Olivieri and I are here to tell the story, while our support team’s gig is to keep us alive and fed. They’re an interesting crew. Leo Gonzales Mulanovich is a Peruvian whitewater kayaker and TV adventure show host. George Olah is a Hungarian scientist who came to the amazon to research the vibrant macaw population here.

Our expedition leader is Cesar Lazo, the most experienced guide at rainforest expeditions. his boss, Kurt Holle, invited us here, ostensibly to see if standup paddleboards would work well for bird research. he also wants to know if they can help attract eco-tourists to his lodges deep in the heart of the Peruvian Amazon.

Completing our group are three local boatmen that rainforest expeditions hired to skipper the outboard-powered wooden canoes that haul us, our inflatable standup boards and copious amounts of gear upriver. We look like a floating REI warehouse sale.

On the first day, the boat takes us upstream 60 miles into the heart of the amazon and the lodge we’ll base out of. The water is murky brown, and the air is sticky. The guides laugh at us when we mention we’re too scared to go to the bathroom after hearing that a local parasite may crawl up inside us and destroy any possibility for future procreation or ability to use the bathroom. I don’t find the humor.

Being girls, Mariko and I thought we’d be in bikinis the whole time. after all, the amazon feels like a sauna. instead, as a futile defense against the ravenous bugs, we cover ourselves with every layer of clothing we can find. Ultimately it doesn’t matter. Any exposed skin quickly becomes a buffet for the Jurassic sand flies. DEET, which we apply in massive quantities, has no discernible effect on them.

“Ho yeah! Look at my ankles!” I look down at where Mariko’s thin ankles should be. instead I see a swollen mass of red bug bites covering all exposed skin from her shoe to her pants legs. Cankles. “I look like some tourist,” she says, with twinges of Hawaiian pigeon poking through her voice.

Mine don’t look much different, except that I’ve scratched them raw knowing full well they’ll scar. But I need instant gratification to soothe the itching.

Mariko barely complains; she mocks me and hands over the aloe, hawaii’s miracle cure for anything skin related.

Meanwhile I’m scrounging for alcohol, wondering why we don’t have a bottle of pisco in our packs. i’m a one-beer wonder but would happily down an entire bottle of Peru’s famous rotgut to take my mind off the itching.

At night, we wrap ourselves in mosquito nets, listen to the incessant jungle sounds, and pray that no jaguars enter our open shelters. Mariko and i share a tent, as well as endless laughter and jokes about getting swallowed whole by a wild animal.

The first morning, they wake us at 4 to check out birds.

Bird watching? really? after days of travel, this is our introduction to the mighty amazon? Mariko and i laugh deliriously and drag our sleepy selves out of bed to go see the birds.

The guides take us to a clay-lick––a mineral-

rich cliff where wild macaws feed on calcium and other nutrients from the soil thought to neutralize the effects of the toxic fruits they eat.

The show is better than anything I’ve seen at a zoo. Thousands of wild macaws gather here––scarlet, blue and gold, red-bellied and BLUE Headed. They feed, chirp fly, mate, squabble and converse. My appreciation for bird watching is forever changed and i resolve to stop complaining. we go back to the lodge, leave behind as much gear as we can, and travel another seven hours by boat farther south. we reach rapids and thick greenery, finally stopping to set camp when we can no longer pull our boats upstream.

It’s finally time to paddle. we pump up the boards, put together the three- piece paddles, swat at bugs, and surf until dark on a knee-high standing river wave conveniently located right in front of our campsite. Surfing knee high waves is like taking a shower after weeks of being buried in the mud.

We feel back in our element even though we’re still scared of all the unknowns below.

In camp, our guides tell us this isn’t the rainy season. The thunder starts on cue. we run to the canoe just in time to escape a torrential downpour as our tents blow into the river. i sit in the boat and whimper. as usual, Mariko just laughs.

Then Mariko points to my shoulders and counts 53 bites on my right one alone along with the hundreds on my ankles. she looks down at her own feet and sees a similar display of bumps resembling chicken pox.

The rain finally stops and we crawl into our wet tents cringing about how many bugs manage to crawl in with us despite our best efforts to keep them out.

At first night we finally get ready to paddle downriver. The first section is full of gentle rapids, and the whole time i feel like I’m going to throw up. it’s not that the paddling is hard, but every turn, every lull in the river, and every swampy looking section makes our hearts race in fear of critters and of the unknown lurking below.

Plus, it’s hot, very hot, and still only 8 in the morning. Mariko is tougher than i am. she paddles the rapids with ease and a smile.

Chase spots a scenic section a few hundred yards ahead and tells us to wait behind so he can set up his camera on dry land. Mariko and i both have to pee. Mariko is a seasoned camper, but now even she is scared to expose flesh to the amazonian bugs.

While i block for Mariko (even though there is no one around for miles), i see Chase sprinting across the river. we assume he’s trying to set up a scenic shot, but later that evening we learn that a small caiman had bumped his board, sending him paddling for his life. The guides laugh at him.

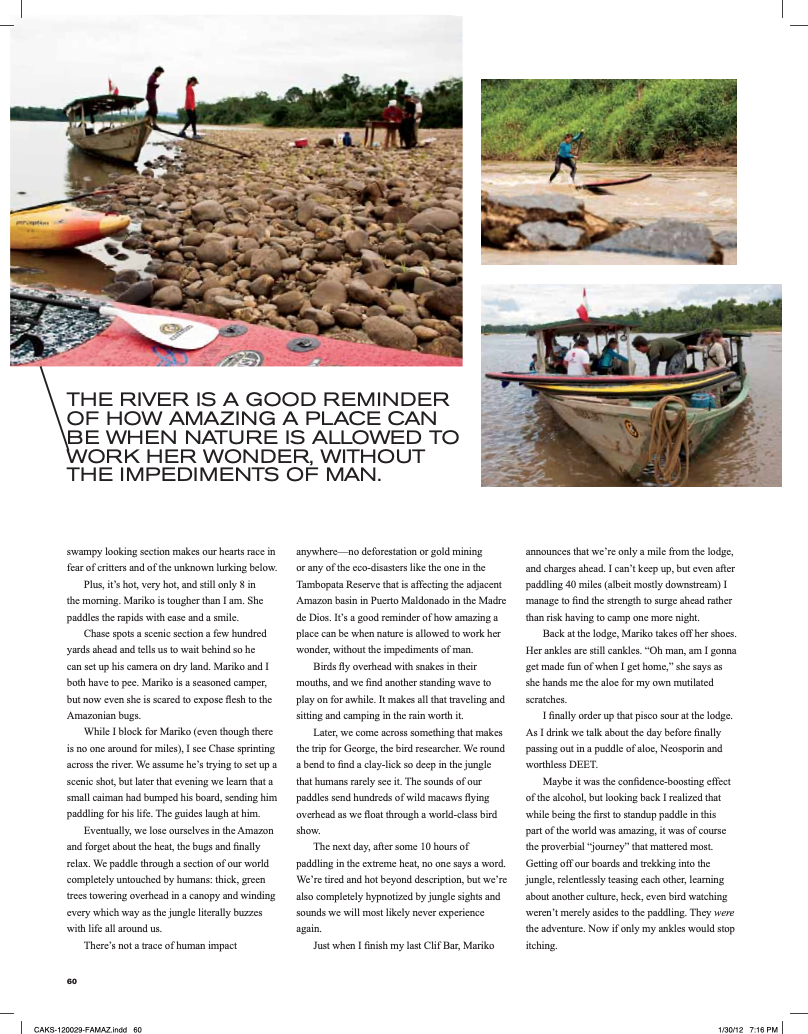

Eventually, we lose ourselves in the amazon and forget about the heat, the bugs and finally relax. we paddle through a section of our world completely untouched by humans: thick, green trees towering overhead in a canopy and winding every which way as the jungle literally buzzes with life all around us.

There’s not a trace of human impact

THE RIVER IS A GOOD REMINDER OF HOW AMAZING A PLACE CAN BE WHEN NATURE IS ALLOWED TO WORK HER WONDER, WITHOUT THE IMPEDIMENTS OF MAN.

anywhere—no deforestation or gold mining or any of the eco-disasters like the one in the Tambopata reserve that is affecting the adjacent amazon basin in Puerto Maldonado in the Madre de dios. it’s a good reminder of how amazing a place can be when nature is allowed to work her wonder, without the impediments of man.

Birds fly overhead with snakes in their mouths, and we find another standing wave to play on for awhile. It makes all that traveling and sitting and camping in the rain worth it.

Later, we come across something that makes the trip for George, the bird researcher. We round a bend to find a clay-lick so deep in the jungle that humans rarely see it. The sounds of our paddles send hundreds of wild macaws flying overhead as we float through a world-class bird show.

The next day, after some 10 hours of paddling in the extreme heat, no one says a word. we’re tired and hot beyond description, but we’re also completely hypnotized by jungle sights and sounds we will most likely never experience again.

Just when I finish my last Clif Bar, Mariko announces that we’re only a mile from the lodge, and charges ahead. i can’t keep up, but even after paddling 40 miles (albeit mostly downstream) I manage to find the strength to surge ahead rather than risk having to camp one more night.

Back at the lodge, Mariko takes off her shoes. her ankles are still cankles. “oh man, am i gonna get made fun of when i get home,” she says as she hands me the aloe for my own mutilated scratches.

I finally order up that pisco sour at the lodge. As I drink we talk about the day before finally passing out in a puddle of aloe, neosporin and worthless deeT.

Maybe it was the confidence-boosting effect of the alcohol, but looking back i realized that while being the first to standup paddle in this part of the world was amazing, it was of course the proverbial “journey” that mattered most. Getting off our boards and trekking into the jungle, relentlessly teasing each other, learning about another culture, heck, even bird watching.